Why Don’t They Just Leave?

Originally posted on Frontlineresponse.org.

“When I first tried to leave him, I left for a few hours and went right back. It was hard. I loved him. He was my world. Watching TV didn’t feel right if he wasn’t there. Sometimes, I just thought about leaving, and then I would talk myself out of it because leaving meant being without him. And that was something that I was not ready for at the time.” - Marisol (White & Lloyd, 2014)

Survivors of commercial sexual exploitation experience rape, physical assaults, disease, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even murder. According to researcher Melissa Farley, 89% of individuals in prostitution want out. Rarely are these individuals held with chains or in cages. So, why don’t they just leave?

Surprisingly, victims don’t leave because their brains are functioning exactly the way they were designed to function — to ensure survival.

Stockholm Syndrome — or trauma bonding — describes the expression of positive feelings toward a captor and negative feelings toward those on the outside trying to win their release.

Psychologist Dee Graham (Graham et al., 1988) identifies four factors that need to be present for Stockholm Syndrome to occur:

a perceived threat to survival and the belief that one’s captor is willing to act on that threat

the captive’s perception of small kindnesses from the captor within a context of terror

isolation from perspectives other than those of the captor

a perceived inability to escape

We must consider childhood trauma, child development, and attachment theory to understand trauma-bonding.

Attachment theory states that an infant needs to develop a relationship with a primary caregiver for successful social and emotional development. When healthy attachment between a child and primary caregiver does not occur due to abuse, neglect, or displacement, it causes disturbed perceptions of who is safe and who is dangerous. Any caregiver can become the principal attachment figure if he or she provides the most care.

Both trauma-bonding and attachment are focused on an individual’s relationship with the person on whom the individual’s survival depends. The pimp/trafficker relationship exploits this vulnerability in many ways, including referring to the group of women he exploits as “The Family” and requiring the women or girls to call him “Daddy.” The pimp/trafficker becomes the individual’s primary attachment figure.

Complex trauma is defined as a trauma that occurs repeatedly and cumulatively over a period of time within the context of primary relationships, or “family.”

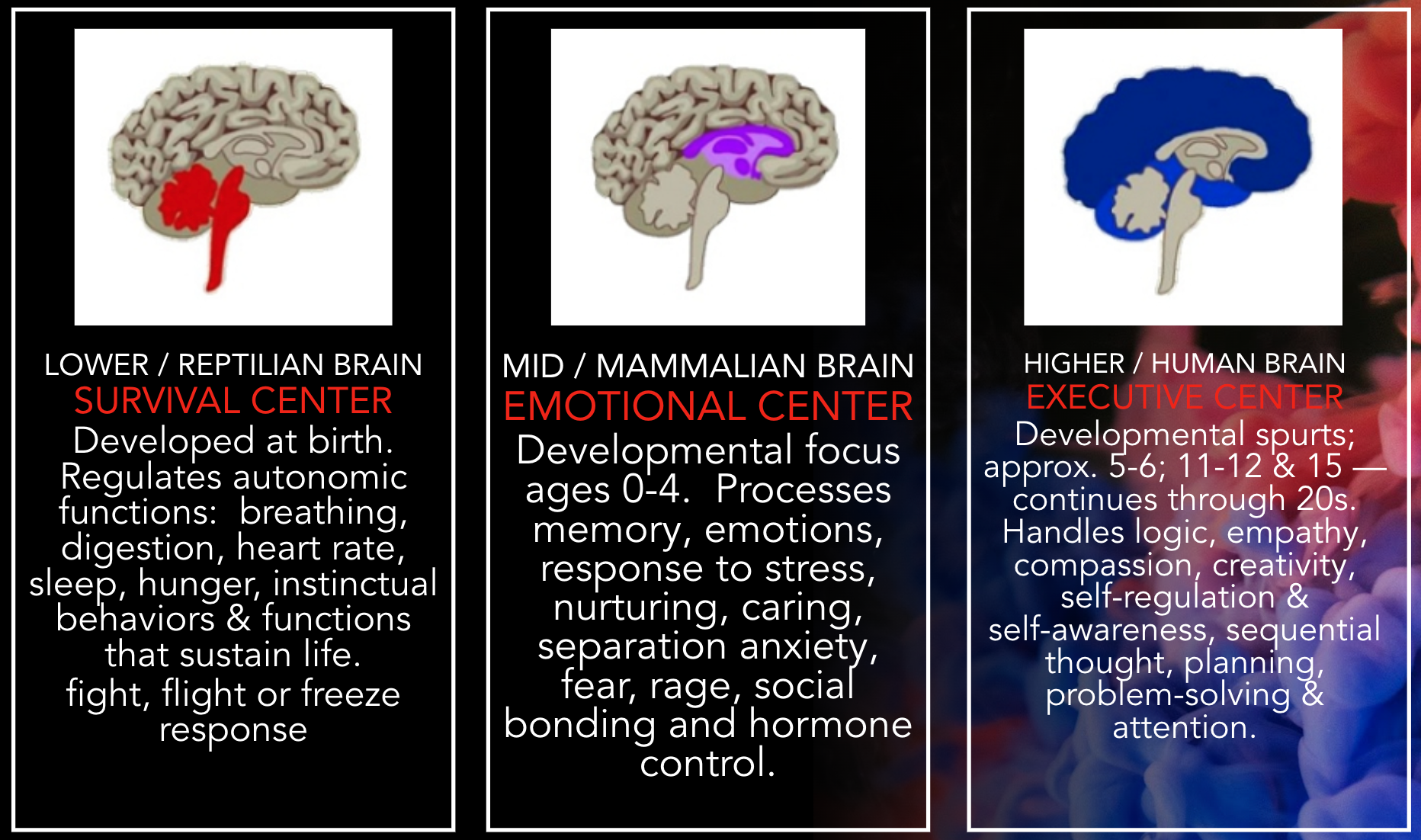

Trauma is held in the lower part of the brain that is developed at birth. This area of the brain regulates autonomic functions, like breathing and digestion, and instinctual functions, like the fight, flight, or freeze response. When trauma occurs, we move out of our prefrontal cortex (or human brain) and move into our survival center.

For example, if a person is chased by a bear, the person will either run away, play dead, or prepare to fight the bear. This is not a decision. It happens automatically. We are wired to survive.

For someone who has experienced complex trauma, he or she is likely to remain in the survival center. When they are there, they cannot access their prefrontal cortex until they feel safe again. This explains why it’s hard for the women with whom we work to consider issues like cause and effect, delayed gratification, and investment in the future. When they are in the fight/flight/freeze response of the survival center, we must focus on establishing safety.

But for survivors of complex trauma, unsafe often feels safe, while safe often feels unsafe.

According to Dr. Bruce Perry in The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog:

“As you learn anything, in fact, your brain is constantly checking current experience against stored templates — essentially memory — of previous similar situations and sensations and asking, “Is this new?” and “Is this something I need to attend to? … These templates are formed throughout the brain at many different levels, and because information comes in first to the lower, more primitive areas, many are not even accessible to conscious awareness … The brain tries to make sense of the world by looking for patterns. When it links coherent, consistently connected patterns together again, it tags them as “normal” or “expected” and stops paying conscious attention” (Perry & Szalavitz, 2017).

Survivors build up a tolerance for abuse and consider abuse to be “normal” and, therefore, the brain marks it as “safe.” In fact, some survivors have said that the abuse of their pimp made more sense to them than the erratic abuse of their parents.

“I don’t get the money, we don’t eat. I understand why he beats me.” - Dominique (Schisgall & Alvarez, 2007))

A truly safe place is novel and therefore scary.

“I was on edge when I got into the Out of Darkness Safe Home. Everyone was so nice, and it was so quiet. I was terrified. What is so messed up is that I knew I was safe -- I just didn’t feel safe. I felt much safer with my pimp who regularly abused me. It made me feel like I was crazy.” - M

References

Graham, D. L., Rawlings, E., & Rimini, N. (1988). Survivors of terror: Battered women, hostages, and the Stockholm Syndrome. https://psycnet-apa-org/record/1988-97676-010

Perry, B. D., & Szalavitz, M. (Directors). (2017). The boy who was raised as a dog: And other stories from a child psychiatrist's notebook--What traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. Hachette UK.

Schisgall, D., & Alvarez, N. (2007). Very young girls [Film]. Showtime.

White, S., & Lloyd, R. (2014). A survivor’s guide to leaving. Girls Education and Mentoring Services.